Putnam 2017 A1

Let $S$ be the “smallest” set (i.e., any other set is a superset) of positive integers such that:

- $2 \in S$

- $n^2 \in S \implies n \in S$

- $n \in S \implies (n+5)^2 \in S$

Which positive integers aren’t in $S$?

Since one rule has a square and the other undoes a square, it’s tempting to combine them:

If $n$ is in $S$, $n+5$ is also in $S$. This already tells us a lot. First we know that 2 + 5 = 7 is in $S$, that 7 + 5 = 12 is in $S$, and so on: 2 more than any multiple of 5 is in $S$: 2, 7, 12, 17, 22, 27, 32, …

But more generally, it hints that we maybe only really need to worry about things in $S$ modulo 5. For example, if we knew that 3, 4, 5, and 6 were also in $S$, we would know that $S$ has to contain all numbers greater than 2.

Given the mod 5 hint, let’s take a look at what our two operations do mod 5.

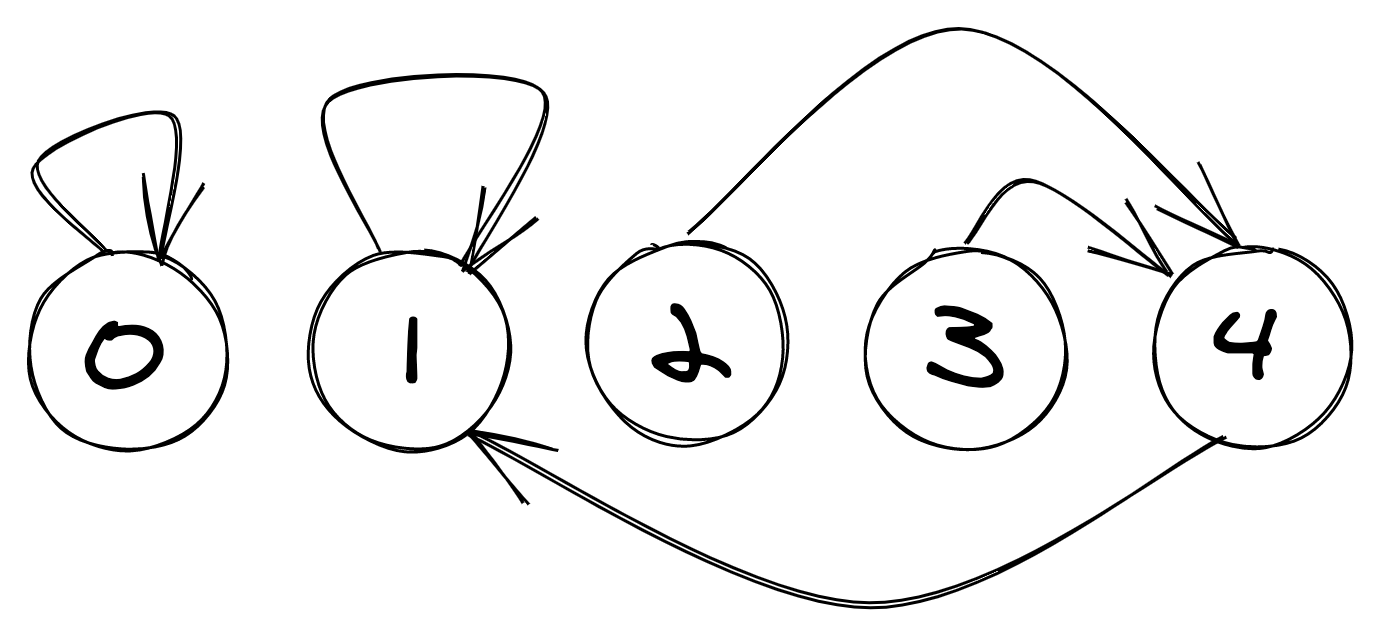

What does squaring do mod 5?

0 stays at 0, 1 stays at 1, 2 goes to 4, 3 goes to 4, and 4 goes to 1.

And because adding 5 doesn’t change where we are mod 5, the picture for $(n+5)^2$ is the same.

Two interesting things to note:

- 0 is an island all by itself

- Everything else eventually gets to and stays at 1

This is powerful. We know from before that if we get something that’s 1 mod 5 into $S$, we can then get any sufficiently large number that’s 1 mod 5 into $S$. And because repeatedly squaring something that’s 1, 2, 3, or 4 mod 5 will get us to something large that’s 1 mod 5, if we can get anything that’s 1 mod 5 into $S$, we can keep applying squareroots to get to 1, 2, 3, or 4 mod 5.

A wrinkle is that we can’t get 1 itself to be in $S$. Normally squaring an integer makes it bigger, which allows us to be “sufficiently big”, but the exception is 1, which is itself squared. This, combined with the fact that rule 3 only ever forces bigger things into $S$, makes it clear that we can’t ever force 1 into $S$.

Well, starting with 2, if we apply rule 3 twice, we’ll get something that’s 1 mod 5. This is implied by the diagram above, but specifically, we have:

From here, we can keep adding 5 to get to any number larger than 2916 that’s also 1 mod 5, which then can get us to 3, 4, and 6 via squarerooting. Again, we know this must work because of the diagram and because squaring makes things bigger, but specifically:

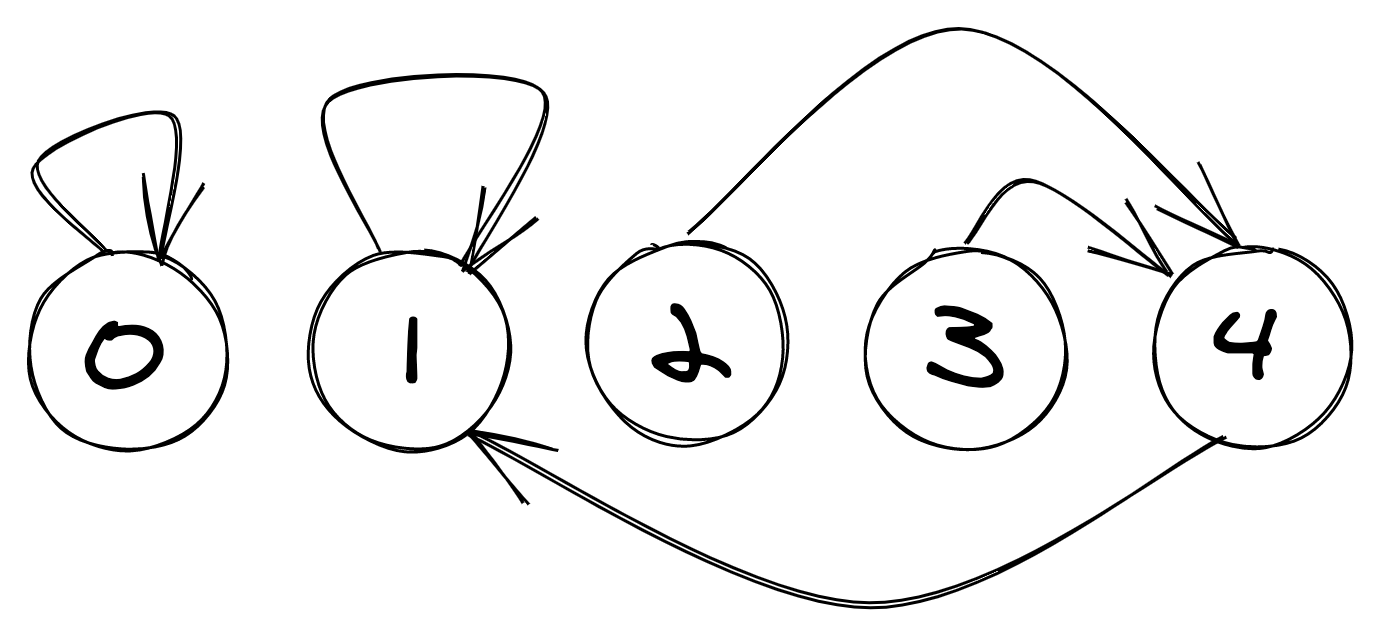

We had $2 \in S$ from before, so this forces everything that’s not a multiple of 5 into $S$ (except 1). But have we proved that it’s impossible for rules 2 and 3 to force a multiple of 5 into the set? Let’s take another look at the diagram:

This is the diagram for squaring mod 5, but if we reverse the arrows, we get the diagram for squarerooting mod 5. The important thing to note is that even if you reverse the arrows, 0 is totally isolated: the only way for something squared or something squarerooted to be a multiple of 5 is if the thing you started with was a multiple of 5.

And we’re done! $S$ must contain everything except 1 and multiples of 5.

Inspired by Michael Penn’s video. Drawings by Excalidraw.

↩ May 23, 2020